When Butch Johnson was first rescued by the passing light airplane, he told his rescuers that he had “escaped from a shooting in which three of his companions were slain.” And then added his story about a strange, lone snowmobiler. But by the time he got to court, almost one year later, both the defense and prosecution were ready to present the videotaped, two-hour twenty-minute confession that he gave to troopers. It had become a case of analysis paralysis.

I don’t know what happened. I wish I did. I killed them. I’m sorry I did. I wish I knew what happened. Honest I do.

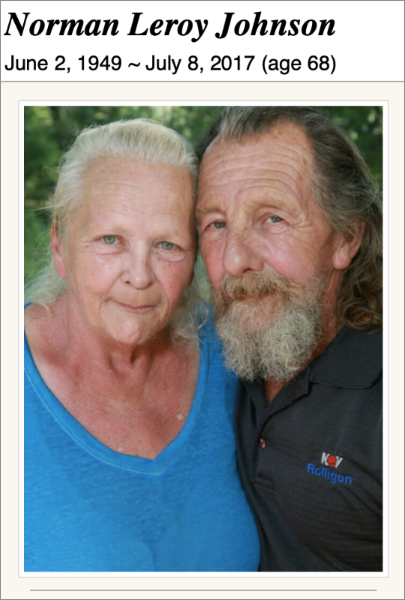

Norman Leroy Johnson at his confession

When Johnson finally broke during his interrogation, he told a ghastly tale of emptying his rifle into the tent, then grabbing another rifle and firing all its shells. And finally shooting Freddy Jackson as he stumbled out of the tent. The prosecution played the videotaped confession at his trial, an Alaska first. His parents were in the courtroom, sitting sober-faced.

Diminished Capacity

His defense at trial was based on an analysis that, at the time of the slayings, Butch was suffering from a mental disease or defect, such that he was not responsible for his actions. That argument is often called the “diminished capacity” defense. Johnson’s attorney was also ready to argue that Butch Johnson had helped one of his victims skin out a caribou and was “emotionally shocked to find a baby caribou inside the mother.”

His parents added that his prior hunting experience was limited to rabbits — in California, where he grew up.

Defense attorney William Fuld of Anchorage also told the court that Johnson feared his hunting companions would harm him, felt distress about being alone among people who spoke a “strange language,” and that the sight of blood on his first hunt prompted him to kill the three men. It was an interesting analysis that strained credulity.

Analysis Turns Bizarre

There was testimony, too, that Johnson was below average intellectually. It was also said that his conduct was not entirely normal, if only because his fall off the snow machine gave him a motive of revenge. Revenge, his attorney said, for the humiliations he suffered as a result of the fall. The psychiatrists piled on. One called his actions a “psychotic break.” Another — Dr. Barbara Ure — claimed that “[H]e did not get up to urinate, he did have an erection, not a sexual sort of thing but in a sense of asserting his identity, [and] preserving his survival.”

It’s entirely possible that Johnson panicked and thought he acted in self-defense. He may have been openly psychotic; I think he probably would have acted mostly from fear.”

Psychiatrist Dr. J. Ray Langdon

There was even a bizarre analysis that called him “autistic.” And went on to define autism as an example of “one who thinks the world revolves around him.” Clearly, these experts had a lot to learn in their analysis of people on the spectrum.

Panicked or Premeditated

Dr. Walter Rapaport, a prosecution psychiatrist, countered that Butch Johnson had the capacity to premeditate his act and understood it was wrong. It was Rapaport’s belief that there was no sign that Johnson was suffering from an illness that would prevent him from knowing the nature and quality of his act.

Rapaport based his opinion on the previous testimony of two defense psychiatrists, the results of a battery of psychological tests administered to the defendant shortly after the murder and reports of the defendant’s conduct following the shooting. That included his ability to relate a convincing — though ultimately false — tale about what happened at the hunting camp.

But when the psychiatric and police testimony ended, everything came down to one man. Judge C.J. Occhipinti. That’s because Butch, his lawyers and his family had decided upon a non-jury trial. Perhaps, they thought, a judge could better understand the intricacies and nuances of the evidence.

Guilty

Ultimately, Judge Occhipinti found Johnson guilty of three counts of second degree murder and sentenced him to life in prison. While he’d turned down a plea of criminal insanity during the trial, Occhipinti left the door open for possible parole. On appeal, the Alaska Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the life sentence should stand.

Robin Barefield writes that “Johnson served most of his time in California, and to the dismay of the residents of Kiana and the Alaska State Troopers, Butch was released on parole after serving only four years in prison.”

with wife, Laura

At a young age he went to live with his parents in Anchorage, Alaska. After a short stay he moved back to California, where he met the love of his life.

Norman Leroy Johnson obituary, July 8, 2017

Johnson died in 2017 at age 68, leaving a wife and two children behind. His obituary made only a glancing reference to his troubled youth.

But, even two years after Johnson’s death, law enforcement in Kiana was still an afterthought. In a 2019 article, KTOO news found that the village only had one Village Safety Patrol officer for its 421 residents. That was Annie Reed, 49, who was outnumbered by local sex offenders, 7-to-1. Hers was not an isolated case; the problem is endemic in Alaska Native villages across Alaska. Somewhere out there is another Butch, just waiting to happen.

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2022). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.