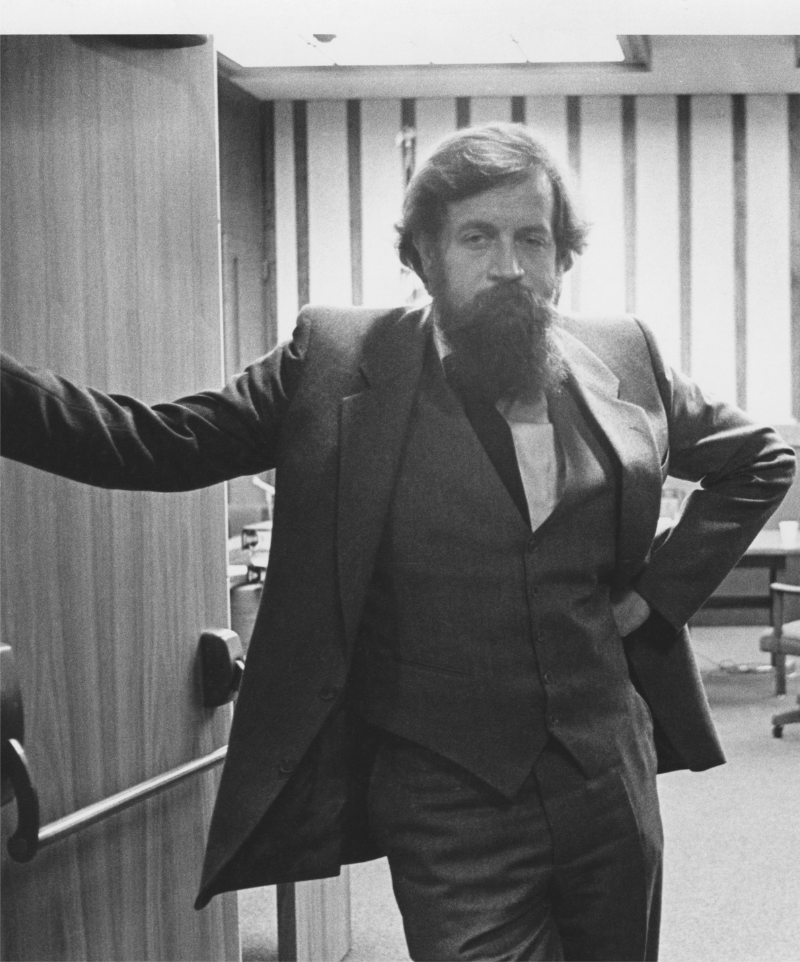

March 11-18, 1986 After a half day of nailing Larry Demmert, Jr. for his presumed drug use, the following day saw defense attorney Phillip Weidner filet him. Indeed, for the next five days, Phillip Weidner harangued Larry Demmert mercilessly. If there was one comfort for the Libby 8 skipper, it was that he had his own attorney in the courtroom to protect him. That fact notwithstanding, Weidner hit hard on his twin themes of drug addiction and police intimidation.

Weidner cunningly referred to Demmert’s pre-grand jury interview as an “interrogation.” Images of bright lights and snarling detectives came to mind. To underscore that impression, Weidner asked, “In this interrogation they were yelling at you, correct?”

“Off and on, yes,” Demmert replied.

That John Peel’s former skipper couldn’t remember the substance of the interview only spurred Weidner on. When Demmert requested the transcript so he could jog his memory, the defense attorney hit him hard. “Is that because you can’t recall now?” he asked sarcastically. “Or you want to make sure you say the same things now?”

“Because I can’t recall,” Demmert insisted.

The longer Weidner cross-examined the man across those five days, the more he pushed the boundaries. If it was drug use that made Demmert malleable to police suggestions, then Weidner wanted to make that known. He seemed absolutely determined to have him answer all manner of questions about drugs, despite the judge’s ruling that most of those questions were out of bounds.

(copyright Hall Anderson)

Things got especially dicey when Weidner asked a series of broad questions about Demmert’s use of sleeping pills. Each time, his inquiry elicited an objection. The questions, the opposing attorneys said, were outside the time frame specified by the judge. Judge Schulz sustained the objections, but Weidner kept at it. Finally, the judge reached the end of his patience. “We’re dealing with the time frames in September of ’82 and other times when this witness has made statements,” Schulz bluntly told Weidner. “Please direct your questions accordingly.”

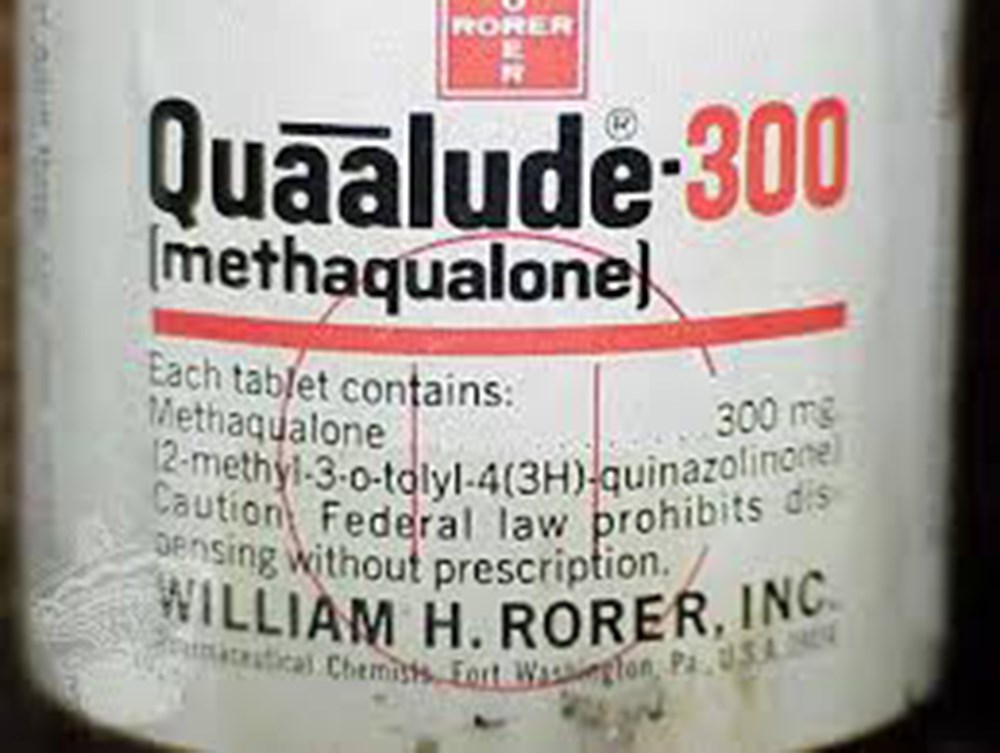

The defense attorney obeyed the judge’s warning, but kept right on pushing. From sleeping pills he went to quaaludes. Although Demmert denied that he was taking quaaludes at the time of the grand jury, he never denied having taken the drug.

Weidner then asked if police told Demmert he was a suspect in the murders, that John Peel was pointing the finger at him. (Shown composite drawings of the suspect, Peel said they looked like Larry Demmert, whom he called “pizza face and glasses.”)

Demmert denied the allegation, but Weidner insisted that police used that information to pressure him into providing false testimony at the first grand jury.

Prosecutor Bob Blasco rose angrily to protest. Weidner’s persistent skirting of the rules had started to take its toll. “Your Honor, I’m going to object,” Blasco said. “This Court went over this and entered orders as to that I strongly object.”

“Sustained,” replied the judge.

Weidner kept at it. He seemed to have five questions for every one of Demmert’s answers. It didn’t take long before Blasco had heard enough. The emotional temperature in the courtroom, which had been hot since the start of Weidner’s latest round of questions, suddenly got hotter.

“You gentlemen can get out your checkbooks.”

Judge Thomas Schulz

In exasperation, Bob Blasco lost track of who he was talking to — which should have been the judge — and started arguing with Weidner. Weidner argued right back. Both men bristled with anger. The judge needed to put a stop to it, before he lost control of his courtroom. After sending the jurors to the jury room, he lashed out at both attorneys.

“You gentlemen can get out your checkbooks,” he said heatedly. “Right now. Before we go any further, Mr. Blasco and Mr. Weidner, I fine you $50.00 for arguing amongst yourselves without addressing the bench. And that’s payable now.”

Five days in hell was at least one too many. And they weren’t even at the five day mark.

Excerpts from the unpublished original manuscript, “Sailor Take Warning,” by Leland E. Hale. That manuscript, started in 1992 and based on court records from the Alaska State Archive, served as the basis for “What Happened in Craig.”

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2020). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.