Phillip Weidner didn’t want a new trial. Barring that, he didn’t want a new judge. That was a problem. Judge Victor D. Carlson didn’t mince words when he handed down his decision. “It is ordered that the Honorable Thomas E. Schulz is disqualified for cause.” And so began the maneuvering.

Weidner immediately appealed the Schulz disqualification. An interesting decision, given that he was at the center of the controversy. He lost. The only consolation belonged to Judge Thomas Schulz. As presiding district judge, he could name his successor. The pointer stopped at Superior Court Judge Walter “Bud” Carpeneti. The decision immediately kicked off a new round of squabbles between the opposing sides.

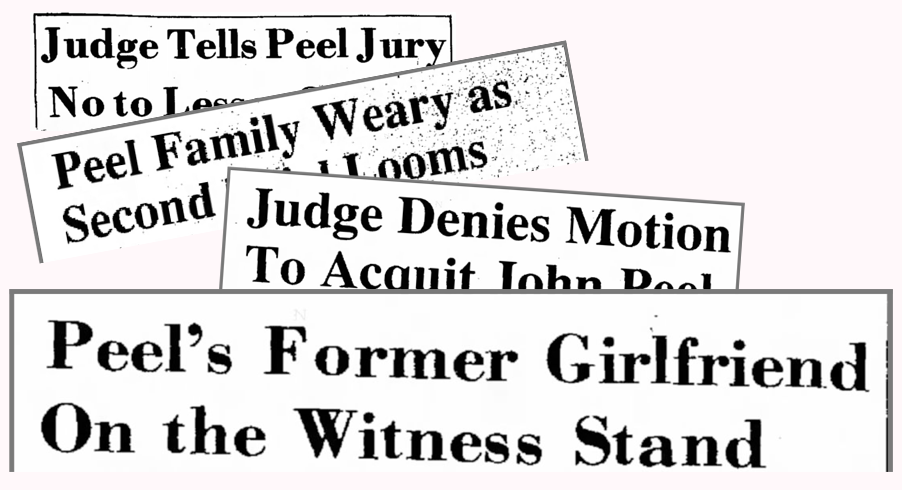

In June of 1987, Bob Blasco went before Judge Carpeneti. He argued that Ketchikan was not the place for John Peel’s trial. Extensive news coverage made it impossible to find an impartial jury. Years of personal derogatory attacks would be difficult to undo.

To bolster his argument, Blasco pointed to the results of 204 questionnaires filled out by potential jurors. More than half of the respondents admitted to bias. The questionnaire also revealed that many prospective jurors feared the financial hardship that would result from jury service.

Phillip Weidner countered that the state was trying to move the trial “because they got beat here in Ketchikan the first time.” Weidner opposed moving it elsewhere. The maneuvering was now in full swing.

In response to the state’s request, meanwhile, Carpeneti asked the state to provide him with a list of newspaper reports that carried false or misleading information. Carpeneti ended up considering seven hours of taped radio reports and more than 300 newspaper articles, although he warned that mere volume of publicity would not be foremost in deciding a change of venue.

As ever, Phillip Weidner’s strategy was to keep the state the busy fending off his multi-layered attacks. A change in the Alaska Governor’s office, for example, led Weidner to ask the Attorney General’s office to change its mind about retrying John Peel. Incoming Attorney General Grace Schaible promised to review the retrial decision made by her predecessor, and interviewed prosecutors as well as Peel’s defense team, before reaching her decision in early May.

“It is my conviction that this case cannot be left hanging in an air of uncertainty,” Schaible said in letting the retrial decision stand. “It is the type of case that should be decided by a jury.”

With that decision, the defense’s strategy seemed to shift toward reshaping the second trial. Carpeneti eventually ruled that the second trial would be held in Juneau. Weidner persisted in opposing the move. Carpeneti turned him away. But the maneuvering would not end.

The defense moved forward on other fronts. They made a motion seeking further discovery about drug use by Larry Demmert, Jr. They filed another motion seeking to preclude the prosecution from “coaching” its witnesses. Another sought information from state, federal and Canadian authorities “relating to drug or smuggling involvement by any of the victims of this case or any persons who may have had a motive or opportunity to commit this offense.” Another sought discovery as to other suspects.

Yet another defense motion sought to reopen and enlarge the defense’s ability to question Larry Demmert about drug use at trial, the assertion being that drugs influenced Demmert’s ability “to perceive, recall and relate.” The defense further sought to suppress all of John Peel’s statements at the Bellingham Police Station.

Judge Carpeneti rejected each one of these defense motions in turn, sometimes because Weidner had submitted the motions without any legal citations to support them, but more often because he saw no reasonable basis for the defense request.

By October of 1987, Judge Carpeneti had seen enough. Judge Schulz’ rulings in this case were declared practically sacrosanct. The maneuvering must stop. The show must go on.

Excerpts from the unpublished original manuscript, “Sailor Take Warning,” by Leland E. Hale. That manuscript, started in 1992 and based on court records from the Alaska State Archive, served as the basis for “What Happened in Craig.”

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2020). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.