By the time the second grand jury went into session, one thing was clear: Weidner’s strategy was starting to cut into the prosecution’s confidence. The first grand jury heard from twenty-four witnesses over a span of several days. The second grand jury would hear from 70 witnesses over several weeks. Mary Anne Henry was taking no chances.

As the grand jury process unfolded, moreover, the prosecution strategy started to emerge. To counter Weidner’s tactic of papering the courtroom with motions, the state was trying to shut off every avenue of escape John Peel’s team tried to open. At the second grand jury, there were witnesses for just about every purpose.

One of the first was the waitress who served the Coulthurst’s their last supper at Ruth Ann’s. She described a man who sat down at the Coulthurst table and drank beer with Mark. She remembered him, she said, because for the ten minutes he sat there, he was in her way. He had sandy brown hair, she thought. Weighed one-sixty. Was in his twenties. If she saw him again, she said, she could probably identify him.

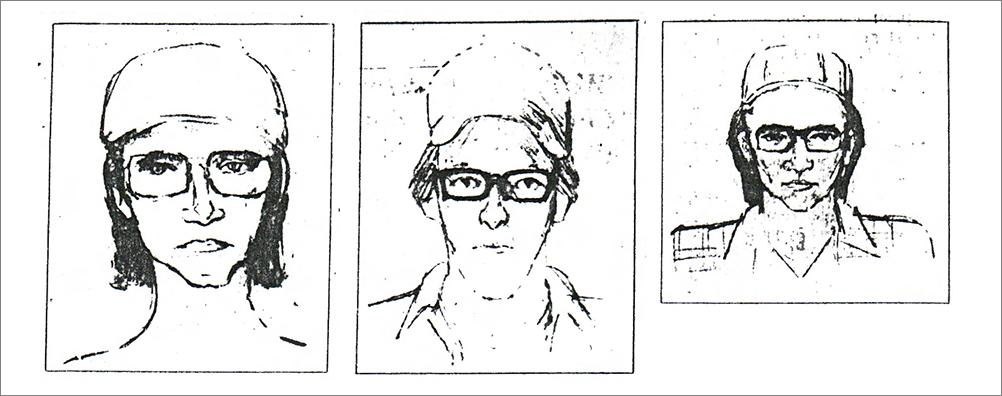

Then there were the identification witnesses — the people who had seen the suspect. They were followed by people who knew John Peel and could presumably vouch for his whereabouts during the time of the crimes. Larry Demmert’s father testified that he had made two trips to the fire and John Peel had made none. They heard from all three of Peel’s former crewmembers, each of whom had wrangled some form of immunity for statements they’d made at the first grand jury. Demmert and Polinkus testified much as they had the first time. Dawn Holmstrom complained that she wasn’t sure some of her earlier, incriminating memories were correct.

A new found emphasis on expert witnesses, however, was the biggest change.

An arson investigator testified, trying to bolster the prosecution contention that the accelerant could have contained a mixture of white gas and gasoline. A forensic anthropologist, who’d examined two bags of unidentified bones, found that the remains represented more than one person. The forensic anthropologist indicated they’d identified seven of the Investor’s eight crewmembers. There was more.

The dental remains from the fire had gone to a forensic dentist who compared them to known x-rays of the victims. He was reasonably certain, he said, that some of the specimens came from Chris Heyman. And, he added, evidence from what he called “Bag Five” showed “consistencies that would lead me to believe that possibly some of these specimens are from Dean Moon.”

If they had Chris Heyman — and if they had Dean Moon — then Johnny Coulthurst was the only one still missing. Henry argued that his body was totally consumed by the fire. The alternative was too absurd to bear: that four-year-old Johnny Coulthurst was missing because he had shot everyone on board and then made a miraculous escape.

Excerpts from the unpublished original manuscript, “Sailor Take Warning,” by Leland E. Hale. That manuscript, started in 1992 and based on court records from the Alaska State Archive, served as the basis for “What Happened in Craig.”

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2019). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter