The idea that John Peel was someone mysterious stood, in a way, as something anomalous. In real life he had, at the very least, a casual friendliness. There was something of the “surfer dude” about him. Life is just a party. But a man on trial for the murder of eight people is not in a position to shout “surf’s up.” Or openly declare, “have another beer.”

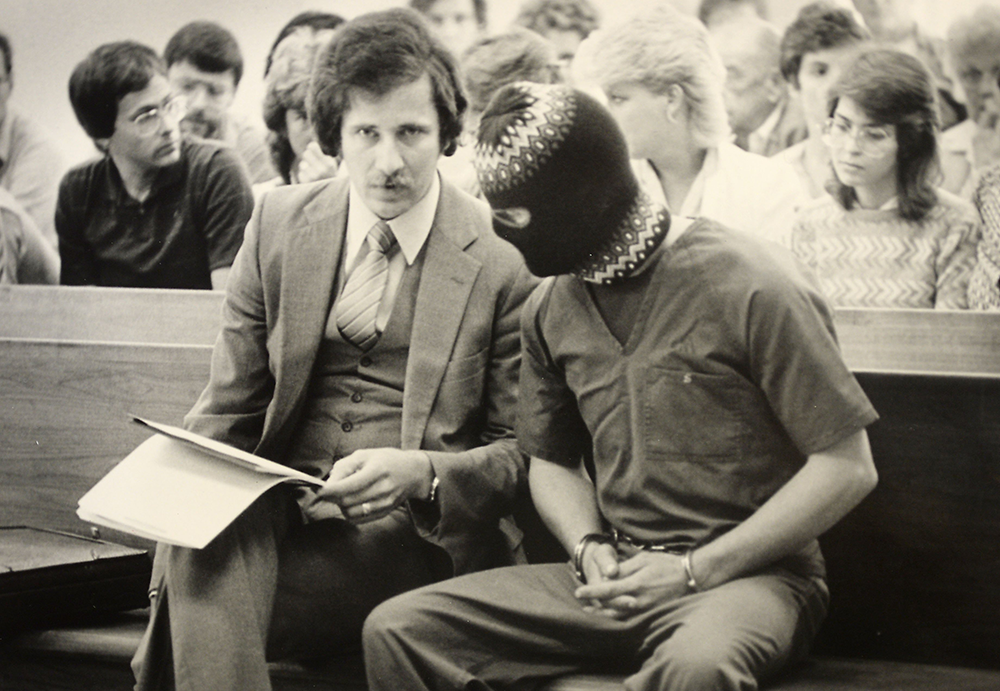

And yet, that image of the mysterious man emerged early on. It came at the hands of his Bellingham attorney, Michael Tario. It was Tario who dressed up John Peel in a ski mask. Maybe he had to. “Identity is everything,” Tario explained. But the overall impact was the creation of a new person. John Peel, the mysterious.

Less Mysterious

At the second trial, the prosecution thought they had a way to make John Peel less mysterious. As the court appearance of Sue Domenowske-Page approached, they entered a motion seeking to make Peel “move, talk and try on clothing at trial.” What that meant was they wanted him to walk like the skiffman, repeat phrases said by the skiffman and wear a flannel shirt and baseball cap like the skiffman.

The tactic seemed a bold one. Or, perhaps, it was an act of desperation. Either way, if it worked, the prosecution might be able to pry loose a positive identification from Sue Domenowske-Page. The nature of memory — and forgetting — had already played a supporting role in both trials. In Domenowske-Page’s case, the defense had previously suggested, through psychologist Elizabeth Loftus, that her memory of the skiffman had been manipulated by suggestive techniques. But Domenowske-Page had come close to a positive identification of Peel at the first trial, and Loftus herself has noted that traumatic memories are often difficult to forget [1].

Reenacting A Meeting in Craig

Whether Domenowske-Page’s memory of the skiffman qualified as an unforgettable, traumatic memory was another matter. But perhaps there was something about John Peel’s physical movement that could untangle her memories. Because, after all, that’s how she’d seen him. Live and direct, in Craig, Alaska.

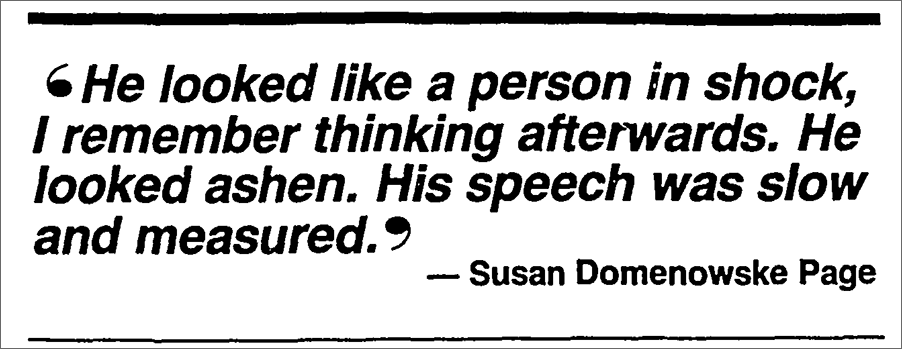

Judge Carpeneti didn’t give the prosecution what it wanted. Domenowske-Page could recall what she had seen and heard on that Craig dock in 1982. She could make note of any similarities in appearance between Peel and the skiffman. What she couldn’t do was suddenly provide a “positive identification” of John Peel. Too much time had passed for Carpeneti’s comfort. For those same reasons- — lack of positive identification, passage of time — John Peel would not have to walk, talk and wear the skiffman’s clothing. The best Domenowske-Page could do was request a closer look.

Domenowske-Page’s actual testimony was less than dramatic. All the years had taken their toll on her memory, as had the fear she’d felt and never quite shaken. On the witness stand, she testified that John Peel resembled the skiffman “in some respects.” That was it. That was the most she could summon.

[1] EDIT: In the recovered memory debate, where she stands as a pioneering researcher, Loftus has other researchers, such as R.J. McNally [Remembering Trauma, 2003], have noted that Holocaust survivors don’t have trouble remembering traumatic events. They have trouble forgetting them. The question of whether Domenowske-Page’s memories were traumatic, therefore, were germane.

Excerpts from the unpublished original manuscript, “Sailor Take Warning,” by Leland E. Hale. That manuscript, started in 1992 and based on court records from the Alaska State Archive, served as the basis for “What Happened in Craig.”

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2021). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.