I was born in the rain city, also known as Seattle. In Mexico, they have a god for that. The Aztec’s call him “Tláloc.” I first met him at the Templo Mayor museum (below). Now, one of my travel mantras is, “sometimes it’s better to be lucky than smart.” And up to that point in our journey, it seemed like we were neither. Could Tláloc change our course? It was worth a try.

Museo Templo Mayor

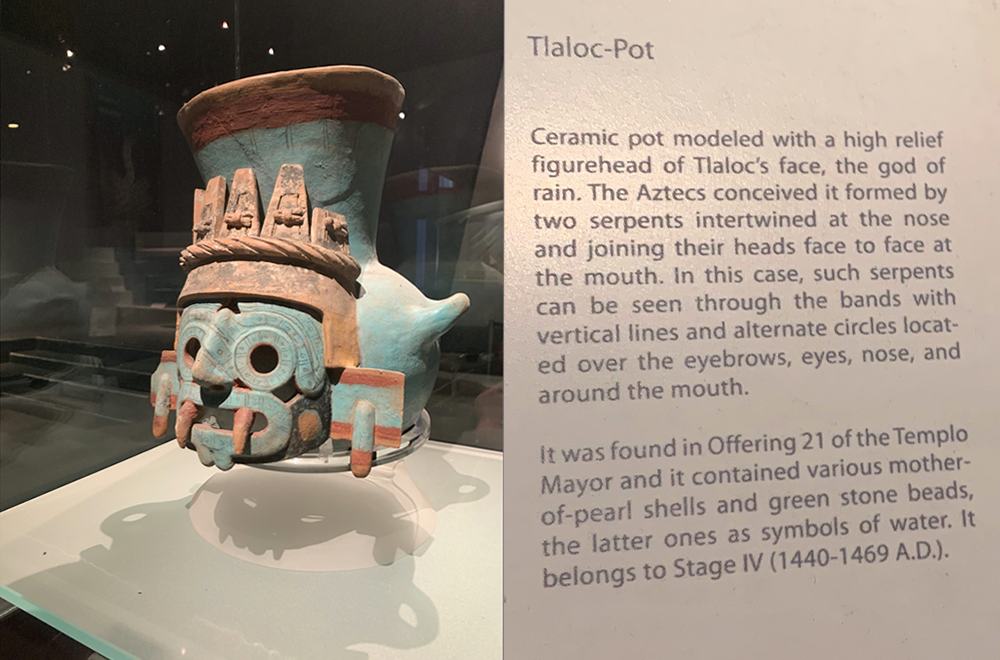

Tláloc actually has his own entry on the Aztec calendar. As the god of rain, lightning and thunder, he was seen as a fertility god. He was widely worshipped as a beneficent giver of life and sustenance. He’s also a wrathful deity, responsible for both floods and droughts. So a mixed bag on the change-your-luck front. We weren’t quite desperate, but…

Fuente de Tláloc

One of the artists inspired by Tláloc was Diego Rivera. He contributed to a major installation in Chapultepec Park that’s dedicated to the diety. It’s an off-the-beaten path location. Why not start there?

Our cab dropped us off at the edge of Chapultepec and we had to make our way to the fountain from the drop-off point. We checked the park map. And my phone map. It was a short walk. Some kids at play temporarily distracted us. Why not? We were on vacation.

Diego Rivera began the Tláloc project in 1952, to commemorate improvements in the infrastructure of Mexico City. What better place to start than the municipal water system? Created at the head of the Lerma River leading out to the city’s reservoirs, Rivera created a massive tiled sculpture of Tláloc, that spanned a pool 100 feet across.

Constructed lying on his back, water used to rush over the rain diety. (That water has since been diverted.) Note the two ears of corn in his outstretched hand. In Mexico, corn is life.

As is characteristic of much of Diego Rivera’s output, he often worked at great scale. The size of the fountain is difficult to communicate in a single shot — or even multiple shots. To compensate for that, I took multiple videos. I thought, yeah, I’ll stitch ’em all together. Someday.

Along with the fountain, Rivera also decorated the Cárcamo de Dolores. It’s a massive sump, once used to control water levels. The water originally flowed through the back of Tláloc’s head (shown below) and into the sump. At some point — right about now — one starts to wonder about the practicality of these ambitions.

As luck would have it, the Cárcamo was open. For a small fee. In the photo below, you can (barely) see the back of Tláloc’s head (top center). The water once ran from the sculpture and then through the elaborately painted interior of the Cárcamo. Not your ordinary sump, the then-underwater mural was called Agua, el origen de la vida (“Water, source of life”).

Teotihuacan

We were not looking for Tláloc at Teotihuacan. But he was there, at the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. I had to look it up, though. And I learned that, depending on who you believe, he was there in plentitude. Water, source of life.

Anthropology Museum, Mexico City

Unbeknownst to me, my first encounter with the diety came at the Anthropology Museum in Mexico City. There is a reproduction of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent and Tláloc is a star. Suddenly we’re no longer in the land of luck.

This is serendipity.