In the first three days of his April 1982 testimony, Sgt. Jim Stogsdill played the role of chronicler, taking over where Sergeant Miller left off. He spoke of the fire and his arson investigation. He spoke of subjecting the nozzle found on the Investor skiff to fingerprint analysis — and coming up empty. And he talked at length about how the investigation wandered in the wilderness for its first year, because “we didn’t have identifiable remains for two of the crewmen.” He also spoke of John Peel, and how troopers came to focus on him as their chief suspect.

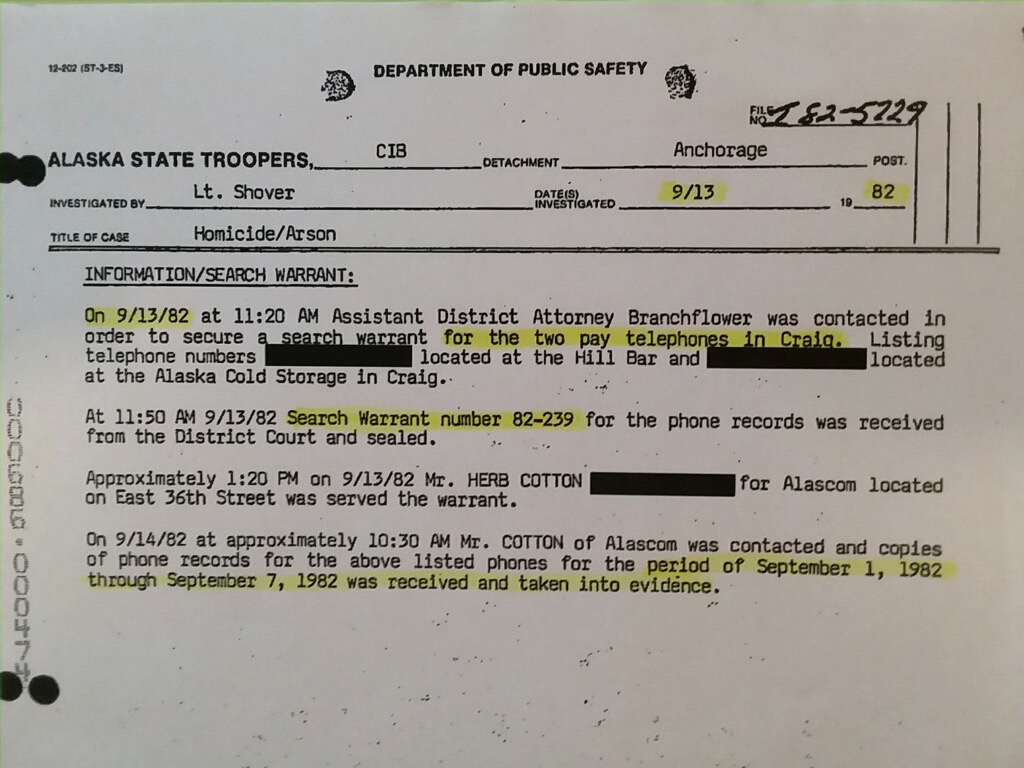

When Mary Anne Henry started asking Stogsdill about telephone records, however, things got nasty. Weidner had long contended that the records weren’t complete and he raised the question again in front of the jury. The defense attorney even went to far as to object to Henry’s characterization that the search warrant for the telephone records was a “court order.”

They were headed back to the wilderness.

“Your Honor,” Henry snapped, “I don’t think we need a lecture on the law here. A search warrant is a court order. Now, if you want me to be specific, I’ll be specific. The court ordered search warrant.”

The judge sensed trouble. He sent the jury back to the jury room. “I’ll settle this issue with counsel,” he told them, “and then we’ll take a break and get back.”

With the jury out, Weidner was even more unrestrained. He got the judge to excuse both Stogsdill and Bellingham Police Detective McNeill. Then he raised the volume on his complaint that the records weren’t complete. The prosecution, he said, was going to start claiming, “didn’t Mr. Peel lie to you, Sergeant Stogsdill, on 11-20-82 when he said that he called his home when the boat was burning. But records have been destroyed.”

(copyright Leland E. Hale)

In the end, even the judge found Weidner’s argument hard to believe.

“What records is it that are lost?” he asked the defense attorney. He was confused, Schulz said, because he had in front of him phone bills for both Earl and John Peel, father and son. Those bills stretched from July through December of 1982.

As it turned out, phone company officials had misinformed Weidner’s investigator. Records had not been destroyed. Outside court, Henry said that prosecutors were unable to find evidence in the records of the call which Weidner mentioned. Asked if he had found the phone call in the records, Weidner declined comment.

They still weren’t out of the wilderness.

Excerpts from the unpublished original manuscript, “Sailor Take Warning,” by Leland E. Hale. That manuscript, started in 1992 and based on court records from the Alaska State Archive, served as the basis for “What Happened in Craig.”

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2020). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.