In the first half of the Eighties, Alaska witnessed a deadly series of crimes, all involving teen killers. From late 1979 to 1985, twelve teen killers committed eight murders. They murdered three cabbies and three members of the Faccio family. That wasn’t all. There was also a 63-year old woman, brutally murdered by three teens who wanted her vintage Buick. The January 1984 murder of a grocery clerk by two teens, aged 13 and 16, who got less than $200 in an armed robbery.

Then, on a Halloween night in 1985, four young men robbed a Carrs grocery store at gunpoint. One of them, an 18-year old robbery suspect, died in a shootout with police. The resulting firefight was intense. The aftermath saw multiple police cruisers riddled with bullets.

Perceptions

These are the kind of statistics that convince everyday citizens that the world is falling apart (which, of course, it always is). There is a constancy to dangerous trends that puts all rational citizens on edge. One of them was Janice Lienhart, the daughter of Tom and Ann Faccio. After the murder of her parents and maternal aunt, Lienhart publicly advocated tougher consequences for teen killers.

“My feeling is that somehow this has got to be balanced. For kids, the bottom line is, do they know they get in trouble or not. If they know they will be punished, they won’t do it… It’s just the way we’re made. If Winona had gotten in trouble for the things she did before, maybe she wouldn’t be in this trouble here.”

Janice Lienhart, Anchorage Daily Times, Nov. 15, 1985

Lobbying for Change

In 1987, Janice Lienhart lobbied newly-elected Gov. Steve Cowper to take a tougher stance on crime. In a “Victim’s for Justice” rally in Juneau, the families of crime victims presented Cowper with a host of victim impact statements. Lienhart told Cowper she believed Winona Fletcher wouldn’t have participated in the murder had she not been a runaway.

“The girl who murdered my family was picked up seven times before that,” she reminded the governor. The solution, Lienhart suggested, was more deterrence.

Two months later, a judge reduced Winona Fletcher’s sentence from 297 years to 135. The Faccio’s other daughter, Sharon Nahorney, complained bitterly. Under Alaska’s 1984 Victim’s Rights Act — which the Faccio sisters were instrumental in passing — crime victims were to be notified of such developments. That didn’t happen.

As if to add insult to injury, Winona Fletcher (below) soon came up pregnant. Which, like it or not, put her into a somewhat privileged category within the jailhouse setting.

There was, however, another truth about teen killers in Anchorage. For that perspective, the Anchorage Daily News turned to juvenile judge Bill Hitchcock. As Hitchcock pointed out, there had been a dramatic increase in violent juvenile crime during early ’84. But, he added, those trends seemed to have leveled off.

“We did have a flurry of activity back there in the early part of ’84, and I think that gave the appearance of an increase in violent crime. But if you look at the statistics on an annual basis, it isn’t borne out. Overall, the total referrals (to juvenile court from police) have actually leveled off and declined in the last two years.”

Juvenile Judge Bill Hitchcock, Anchorage Daily News, June 11, 1985

Impulse Control

Most people, however, don’t (or can’t) think of things on an “annual basis.” And, god knows, the crimes committed at the Faccio household were enough to terrorize anyone. They were, after all, in their own home, minding their own business. It wasn’t difficult for the citizens of Alaska to identify with their plight. Still, there was something missing or — in the case of the Alaska Court of Appeals — overlooked about this thread. The missing concept was “impulse control.”

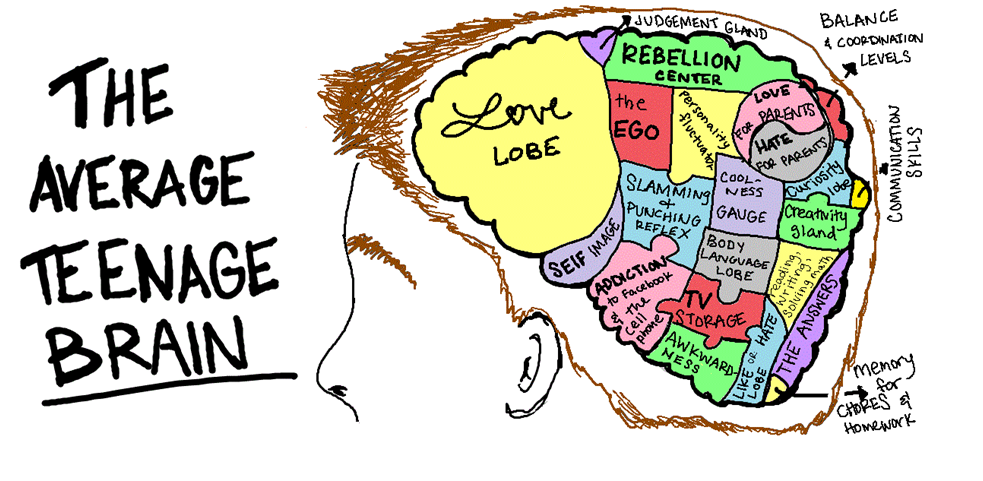

As in, teens don’t have much in the way of impulse control. There is, in fact, a developmental reason, explained by advances in brain science.

Teenage Brain Science

Teens, it turns out, have many more synapses than adults. At the same time, teenagers lack strong connections between the frontal lobes — the seat of executive function, judgment, empathy, and impulse control — and the rest of the brain, where emotions dominate. “Teenagers cannot yet access their frontal lobes for instant decision making” — leading to impulsive actions that even they cannot explain. [1]

Put another way, “the temporal gap between puberty, which impels adolescents toward thrill seeking, and the slow maturation of the cognitive-control system, which regulates these impulses, makes adolescence a time of heightened vulnerability for risky behavior.” [2] As with all things scientific, there are nuances to be acknowledged: some adolescents are worse than others [3].

And for those who doubt the brain scientists? Heed the actuaries who work for insurance companies. There’s a reason car insurance rates are much higher for teens. Quite simply, they get in more car wrecks. Something about risk taking. And a lack of impulse control.

One More Note

All of which leaves us wonder: Should Winona Fletcher have been tried as a juvenile? There is evidence that “sensation seeking peaks around age 19 in males and 16 in females.” Exactly the range Fletcher fell into. That said, there are no easy answers. When such reprehensible acts occur, society often makes a fundamental cry for eyes and teeth.

In Fletcher’s case, the Alaska Court of Appeals decided to avoid the question entirely.

But, in 1994. the Alaska legislature tried to address the issue. They passed what’s called the “Automatic Juvenile Waiver.” Under that provision, a 16- or 17-year-old is automatically charged as an adult if the crime for which they are accused is an “unclassified” or “Class-A” felony. These are crimes like rape, murder, or manslaughter. [4]

Sounds reasonable. Except, of course, it only addresses what happens after the crime has been committed. .

References

[1] Deborah Perkins-Gough, Secrets of the Teenage Brain, ERIC, October 2015.

[2] Laurence Steinberg, Risk Taking in Adolescence: New Perspectives From Brain and Behavioral Science, Sage Journals, April 2007

[3] See also: Beyond stereotypes of adolescent risk taking; Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility; Insight into the relationship between impulsivity and substance abuse from studies using animal models [Google Scholar is a great resource; it includes a trove of studies about deterrence.]

[4] Alaska is not alone.

Copyright Leland E. Hale (2023). All rights reserved.

Order “What Happened In Craig,” HERE and HERE. True crime from Epicenter Press.